So, while the proverbial door had opened, it wasn’t as easy as 1, 2, and 3:

Being stationed at Willow Grove allowed home visits. One weekend, everyone was sitting around the kitchen table when Chico announced his intention to become a fighter pilot. The family burst out laughing. Infuriated, Chico left the cajoling, grabbed his bag, and informed everyone they would not see him again until he had wings. In vain, Antonia tried persuading him to stay to no avail.

With determination being the motivator, Chico wanted to become a fighter pilot. The problem: he was a Marine, whereas it was the Air Force that rescinded the college requirement. At the time, Chico had no idea of the proposed changes when he made his proclamation. Imagine, the gift of a high school diploma allowing him to apply, making the upcoming threat of war work in his favor, except he was in the wrong branch, but those other hands knew. Korea was the godsend, the needed alignment, paving his way to becoming a fighter pilot.

With permission from the Corps, Chico applied to qualify for the ACT (air cadet training) program. Making the cut, the Marines discharged him August 5, 1948, allowing a twenty-four-hour window to become an airman. By August 11, Chico was ready to realize his dream of flying the best any government offered. Now that he was in, all he had to do was qualify again, or be stuck until the new enlistment ended. He had one chance to get it right. He transferred to his first duty station, Fort Slocum, New York, on June 27, 1949.

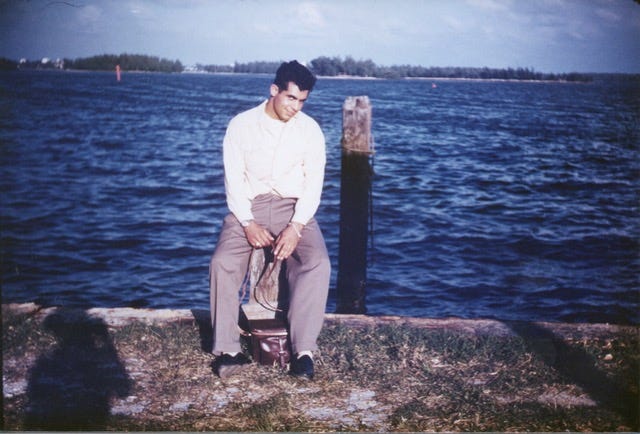

Now, before Chico donned the Air Force uniform, there was a trait he carried. While a Marine, being sharply dressed included boot heels. To maintain a square-edged heel, he installed taps, walking with a click, tapping out a familiar sound, which became his signature trademark: click, click, click!

At Slocum, Chico’s first assignment was guard duty, watching a pilot awaiting trial over black market activities while overseas. Along with another airman, the two guarded the prisoner twenty-four/seven in twelve-hour shifts until a guilty verdict. Chico was then placed on an honor-guard detail as a rifleman, traveling to cemeteries and performing reburials for fallen soldiers from World War II.

Due to conflicts with ACT qualifying, Chico was pulled and assigned to the OSI, serving on jeep delivery details. In between deliveries, he underwent a battery of tests covering math, science, and physics. Basically having to pass a four-year college equivalency test. Competing with twelve other applicants, he was one of four survivors. He then underwent physicals, including dexterity tests. Finally, officers at Mitchell Field on Long Island, New York, interviewed him to see if he had “the right stuff.”

While on base, Chico routinely entered the Adjutant General Department of the 1st Air Force. And sitting at a desk situated where all was visible was a good-looking civil service employee in her second year. Initially, she’d worked in the transportation office generating travel plans for service members. Then, after a promotion, she became the clerk typist for the Adjutant General’s Office and performed general typing and filing. On occasion, the two shared glances, but they did not meet until a mutual friend, Al Sortino, introduced them to each other. Sparks flew and the two started dating.

Maria “Kitty” DeCosmo hailed from New Rochelle, New York, the oldest of five children. Her parents had immigrated from Calitri, Italy through Ellis Island. So, as things took off, before Chico entered pilot training, they married July 3, 1949, at the Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church in New Rochelle. The best man: Carl Eisele. Ann Lalli, Maria’s childhood friend, the maid of honor. The reception took place at the Post Lodge in Larchmont, New York. And for $82.69, the newlyweds honeymooned July 3-7 at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City. From introduction to wedding: three months!

Chico entered the ACT program after serving eleven months in the Air Force and was designated an Air Cadet. He entrained July 11, 1949, joining Class 50D at the 3545th Training Squadron, Goodfellow AFB, San Angelo, Texas.

_____________________

In World War I, flights were three planes. Called a Vic in Britain, a Kette in Germany, fighters maintained loose “V” formations. Peeling in a one, two, three pattern when attacking, a two-pronged feature was built in. The “loose” allowed pilots the ability to scan larger areas and, if attacked, life preservation. The attacking flight could theoretically only snag one fighter, allowing the other two to break and counterattack. Then, when cinematography became vogue, flights tightened, highlighting the “V,” including fighter-pilot cool.

Now, enter WWII and the Battle of Britain. A British fighter pilot, Douglas Bader, introduced a flying style called “fingertip formation” or “finger four.” If one looks at the left-hand sans thumb, the middle finger is Lead. The ring finger is Element Lead; number Two, the index finger; and Four, the pinky. Flying in this formation, Lead protected Two, and Element, Four, while Two and Four covered their leaders.

Throughout the years debates have ensued regarding who invented the formation. Some credit the Finnish (1934); the Germans second (1938); and the Brits third (1938). During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Germany fought with the Nationalists in Spain. Having a shortage of planes, they developed a flight of two called the Rotte. When Werner Moelders appeared in 1938, he created the four, a Schwarm. Although, I wonder, who, when first in combat, and came under attack, yelled: “Hey, they copied us!” You be the judge, but the Brits did coin the phrase: Finger Four.