Within a month he received an Air Medal for completing twenty missions. It covered May 15 through June 25:

First Lieutenant Roland X. Solis distinguished himself by meritorious achievement while participating in aerial flights over enemy-held territory from 15 May 1952 through 25 June 1952. Lieutenant Solis participated in combat missions which destroyed and damaged enemy installations and equipment despite heavy flak and small arms fire. In addition, he engaged in patrol, escort and armed reconnaissance deep into enemy territory during which hostile contact was probable and expected. By his high personal courage and devotion to duty, Lieutenant Solis has brought great credit upon himself, the Far East Air Forces and the United States Air Force.

Now, one of the scariest jobs in Korea: railroad bombing. Where every fighter bomber participated in destroying tracks. It was extremely dangerous, low level, and costly in pilot attrition. Especially when headquarters notified the populace with drop leaf flyers beforehand. Initially, pilots came in at a thirty-degree angle, descended to one thousand feet with 1,000-pound bombs or eight hundred feet with 500-pound bombs and released.

Everything depended on pilots maintaining parallel position with the tracks, descending to the proper altitude, calculating for bomb drift from wind direction and speed, release, and pull out. All the while avoiding merciless anti-aircraft fire. If they survived, they returned to base, reloaded, and repeated.

Once flights commenced, they rolled throughout the day, allowing the Chinese to bring more guns. Their job, save the tracks. Earlier flights had a better chance of survival than later strikes, which consisted of enemy reinforcements launching additional anti-aircraft fire. With the exaggerated loss of pilots, the drop ceiling was ultimately raised to three thousand feet, increasing one’s chance, yet the flyer drops continued. On the politics side, generals were protecting the civilian population … and their jobs.

After destroying rails, the Chinese went through the motions of putting everything back together to move trains supplying the front lines. Primitive as they were, repairing tracks was a manpower project. The best way to accomplish the task—bring in the “coolies” (unskilled laborers), putting them to work. The Chinese improved efficiency by using teams of one hundred men. As soon as flights finished, coolies worked while pilots sometimes strafed to keep them away before departing. Having upwards of one million coolies in reserve to work on rail placement meant tracks went back together quickly. In Korea, life was also cheap. So, for motivation, some were sacrificed at gunpoint to get others to work faster.

Now, if command theoretically wanted to stop trains completely, the next best thing was tunnel-busting. Done correctly, it took longer to repair/rebuild a tunnel and tracks. Better still if staged trains were inside and pilots destroyed them in the process, and tunnel-busting used a form of bombing called “skip bombing.” There were four guys from the wing selected to fly. They hunted for train tunnels and attacked, skipping a bomb into the mouth, timing it to blow up inside. A tunnel meant a mountain. One had to be close to release, pulling hard to clear:

“Another time, I was number Three in the flight of tunnel-busters. Number One went in and skip bombed, number Two went in and skipped bombed, then I went in. I’m looking at the target trying to get the bombs in, and I saw these damn tracers going by me. Some Navy guy in an F-9 saw there was smoke coming out of a tunnel. He didn’t see me; he was going down, and he was going to strafe the mouth of that tunnel. I was between it and him. When I saw those things, man I pulled up, and when I pulled up, he went right under me. I don’t think he ever saw me.” - Roland X. Solis

________________________

Weather itself was a veritable mixed bag in Korea. From stone cold winters with snow to summers nice and hot. Throw in the rainy season, and pilots played havoc. K-2 had a weatherman who predicted the forecast, enabling squadrons to put missions up. The weatherman always hoped if he did the right thing through good weather predictions when the time came, pilots would do right for him. Chet remembered:

Woodrow W. Woodside was the 49th Fighter Groups Weather Officer. Weather forecasting was ancient history compared to today, especially considering there were no weather satellites floating across the heavens. How reticent the Chinese and Russians were in sharing data with us. To say that Woody’s job to accurately forecast the weather in a very remote target area 300 miles north was virtually impossible would be a gross understatement. To say having an accurate forecast of the weather at the target was less than urgent to the fighter pilot upon arrival would also be a gross understatement.

My experience in fighter squadrons has been that even though there is no such thing as a fighter-pilot fraternity there is an informal relationship that borders on there being such a thing. Especially when fighter squadrons are in combat. There isn’t even a second thought about one’s personal safety when there is a need to come to the aid of a fellow pilot in danger. So, yes, I guess there is such a thing as an informal fighter-pilot fraternity. Woody Woodside was a great guy who was always welcomed by pilots, but he just wasn’t one of the fighter pilots.

He had a personal 16mm movie camera and was really dedicated to recording an informal history of the 49th Fighter-Bomber Wing while he was in Korea. He did all the right things, but he didn’t put on a parachute and go share the excitement, so he only got close to being in the inner circle of fighter pilots. Something was missing for him to make that final step regardless of all his efforts.

Most of the interdiction missions flown along the front lines were against targets that were out of helicopter rescue range. In late spring 1952, all the pilots and staff were assembled one morning for a briefing on the All-American Aviation System which was being deployed to Korea for the rescue of downed pilots where neither a helicopter or SA-16 amphibian rescue was possible. The team showed a film of the system depicting how a package would be dropped to the downed pilot who would set up two tall poles about thirty feet apart with a strong nylon cable strung between the poles.

On the end of the cable was a harness which the downed pilot would put on, then go sit down off to one side of the poles. When all was set, the downed pilot would signal he was ready and the C-47 would swoop in and catch the line between the posts with a grappling hook to be winched into the C-47. As simple as that! The demonstration was scheduled for early that afternoon for the pick-up to be made between the runway and taxiway just north of the fighter squadron ramps.

The dummy downed pilot would be about fifty feet above the ground when reeled in as it passed in front of each squadron’s ramp. When the leader of the demonstration team answered questions from the audience, he casually asked if there was anyone willing to volunteer to take the dummy’s place for the ride.

We fighter pilots had pretty well decided we would take the chance if we were sitting on a hill a hundred miles north of the front lines, and had come to the conclusion that was the best alternative to get back home to our wife or sweetheart. Here on the flight line, the dummy would suffice to show us how well everything worked. We began to look around to see if anybody was going to be dumb enough to take that ride. All was quiet for about forty-five seconds. Then out of the blue, “I’ll do it.”

With that, Woody joined the demonstration team. Shortly thereafter, the news had spread throughout the base. By the designated time, those who were not on a mission and virtually everyone else had found a place on the flight line to view the simulated air rescue everyone hoped they would not have to experience. I believe the available combat pilots were at least twenty minutes early and within fifty feet of where they expected Woody to come zooming past.

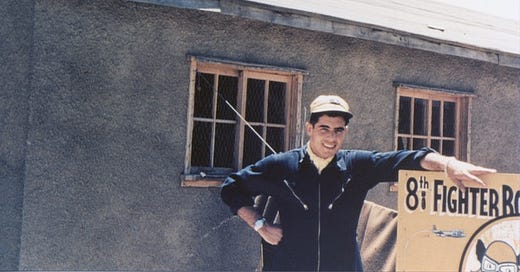

We were present and accounted for when the gooney bird turned base leg for a straight in, descending run on a long final approach to the pickup point. Woody was completely ready for the ride and was holding something in his hands. When the grappling hook caught the line between the two poles, Woody went almost straight up for about twenty-five feet before leveling off about fifty feet above the ground. As Woody approached the 8th FBS ramp, he aimed his 16mm movie camera to make a record of his fighter-pilot buddies welcoming him into their fighter-pilot fraternity!

Really enjoyed the story. Thanks