Try to imagine the physical and mental stress associated with climbing into a fighter cockpit during war. Pilots knew they might not be back on the tarmac after a mission. So, when they stared death in the eye, I believe most wanted someone of the cloth to offer safe travels.

K-2 had a priest. Every day he’d be on the flight line with his crosier blessing each plane. Now, this priest’s staff was special. Instead of a curled end as with a shepherd’s hook, on one end was a fifty-caliber projectile and the other the casing, not what one would expect a man of the cloth to be wielding.

______________________________

When missions required a “gaggle,” pilots who normally flew in other flights came together. On these days Chico and Chet flew in different flights but were able to see the capabilities of the other. Chet was Flight Lead. Chico, not yet. Chet recalled a Fourth of July mission against the North Korean Military School. Chet flew Element Lead in the second flight while Chico was in third flight. They were attacking after the 58th Fighter-Bomber Group.

Chet: We were just lieutenants, who occasionally on the larger missions would be on the same mission but normally not the same flight. [On] July 4, 1952, Chico was in the strike to the North Korean Military School. The 58th, as I remember, had one-thousand-pound GPBs (general purpose bomb). Our target was the mess hall. At twelve o’clock noon, the cadets, actually the officer group, were supposed to sit down for lunch. The 58th made a pass from the east and we came in from the west. We made a feint toward the Three Hole Dams on the Yalu River, [and] then at the last minute, the 58th turned to the west and struck the mess hall with bombs and the 49th came in with napalm.

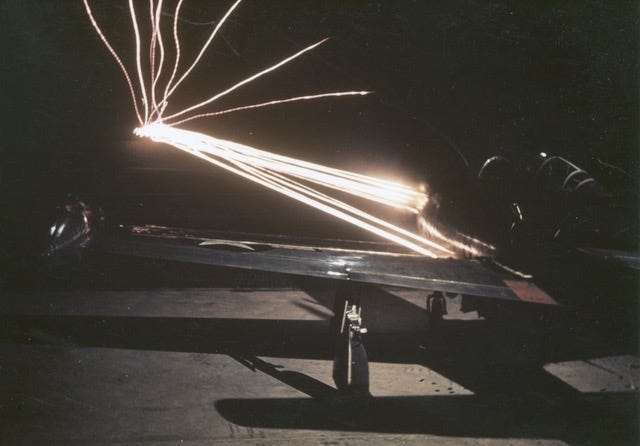

We were briefed to make a 270-degree climbing turn to the left giving middle cover as we went across. As I pickled off the napalm, I looked up and counted thirteen parachutes. The MiGs were up and the F-86s shot down ten. As I went back across the flights behind us from the 49th, were still coming in, in fingertip formation. I went across at about eight thousand feet; there was nobody fighting, but I looked down and there were four F-84s unloading napalm, four MiGs behind them shooting and four F-84s behind them shooting. Everybody was shooting. It was pretty hairy; the Fourth of July flight was a maximum effort. We were there, and Chico was right behind us, not more than thirty seconds.

The sky, bursting with F-84s, F-86s, and MiGs, twisting, turning, rolling, breaking right, breaking left, dropping, speed braking, climbing, trying to survive and remain hunters. In the heat of battle, pilots had to be intensely aware of their surroundings, multi-tasking, praying they were not strafed by errant rounds, having to eject. If they did, their main goal then was to escape instead of becoming a POW or shot while in the parachute gliding to earth.

It must have been surreal to eject, and idly drift while fighters, both enemy and friendly weaved around those descending, rolling, pitching, firing. Some tried protecting as the enemy tried to hasten their descent. When the fighting wrapped, if one returned, he hit the hooch, had a beer, and relaxed, ready to do it again the next day, while those who ejected, evaded capture, became POWs, or were killed attempting escape. If captured, they were abused, mistreated, or broken down mentally, physically, any way possible. And think, PTSD was not an acronym yet created for post-traumatic stress disorder. But, to make the warrior’s life easier, politicians made certain pilots did not attack over the fence.

Now, Pyongyang wasn’t the only target in the game. The Air Force utilized any means possible to upset North Korea in their ability to transport supplies. Earlier, I mentioned the train system. There was also trucking. Both were for the most part run under cover of darkness, allowing pilots two opportunities to “break bad.” One was in a flight of four while the other solo. On both types of missions, few went. On the trucking side, convoy hunting. Once found, a pilot dropped a thousand-pound headache of shrapnel. Chico was fortunate flying both types to attain the magic 100. Night interdiction came along once the squadron commander felt competent he could read a map and compass:

“I’d take off and fly to a point where I’d see the trucks coming out of Pyongyang. They’d reach a certain point and the lights went out. I’d be up there flying around with two VT fuse bombs, one-thousand pounders, and find these points where it’d look like people would be, a checkpoint or something. I’d go there, and drop a bomb, scare the shit out of them, and then look for another and do the same thing. VT fuse was a bomb that went off in the air; it didn’t hit the ground. It went off and just rained everything with shrapnel. That’s why we didn’t drop both bombs together.” - Roland X. Solis

VT, or variable timed, detonated bombs at preset altitudes, then rained hell. Not surprisingly, sometimes things didn’t work out quite right. I guess it could be fortuitous when flying alone: “One night I took off [on] a night mission, where I was up by myself. It wasn’t a two-man thing; I went alone. Up on the front lines, the Americans had searchlights; they had a lot of searchlights, and they’d search the other side. If they saw anything, they’d searchlight it and then shoot at it with whatever they had. One night, it was clear, just clear as a bell, a beautiful night. It had snowed. The moon was out and bright. When I crossed the line, I saw the searchlights were going back and forth. I could see the tracers going wherever they were shooting.

I went up near Pyongyang and found one bombing opportunity. I went down and dropped one bomb, pulled up and went looking for another. I found another and dropped the bomb. When I pulled up, the moon was so bright I could see trucks. I went around and was going to strafe them, which was dangerous. It was a no-no for strafing at night because when you fire, you’re blinded by the muzzle flash of the guns, if you tried to use the pipper and look through the windscreen.

So, I went down and fired short bursts while I looked down into the cockpit. Sure enough, the damned thing just all lit up. At least I wasn’t looking, so I pulled up. I had just raked the convoy. There were four fires—four trucks burning. I said, “I better not do this anymore; I’m going to get [into] trouble.” So, I started climbing and thought, well, that way’s home. I looked back and saw these lights on the horizon and wondered what the hell those lights were. I thought I knew where the hell I was, what I was doing and kept wondering what those damned lights were. They were the searchlights. I was going away from them.

I didn’t realize it until the radio blurts up and says aircraft in X-Ray Easy, you are nearing the fence. The Yalu River was what they called the fence. You couldn’t go across the fence, and I thought “some dumb son of a bitch is lost.” It was me. I looked down at my compass, and I was headed north. I just turned around, turned off my IFF and headed home. That was one night I was not thinking at all.” — Roland X. Solis