The school of pilot discipline commenced July 20, 1949. Some would survive, earning their wings, while others bailed, and governing regulations manifested. Though they trained together, if an officer decided the service was not for him, he resigned. Not so enlisted. If married, wives were visitation only. Uniform inspections were the norm, be it spot or with class. The intent; weed out the weak.

Chico’s first flight was August 15, in the T-6 Texan. One day, awaiting his turn to fly, he eyed a student straddling the fuselage, taking an earful from the IP about his inability to fly. Having reached the breaking point, he erupted: “I do not have to put up with this shit!” Being commissioned, he quit. Chico did not have the same luxury. This was his only opportunity to earn a set of wings, harassment be damned.

Along with class, students flew every day except weekends and usually less than an hour. Sorties started with simple turns and level flight. Trainees then progressed to landings, spins, stalls, forced landings, patterns, and the joy of repeatedly flying until mastered. On September 23, Chico soloed for the first time as a military pilot. Although, to earn those coveted wings, he still had to go through advanced, but he had an obstacle. His IP (instructor pilot) was a B-17 pilot from WWII. He helped mature Chico in more ways than just pilot training. Out of the cockpit, the IP was easy going, soft spoken, reserved. And when the opportunity afforded, after the day’s flying was done, the two discussed life. One of the traits passed; officers did not wear jeans, anytime, anywhere. Chico turned eighty-six before donning a pair. And hailing from the bomber-pilot fraternity, the IP also had a split personality.

In the air, he demanded precision, proper protocol, and finesse, letting Chico know on the spot when he messed up. Now, the obstacle. First Lieutenant Ogelsby, the IP, felt washout rates for fighter pilots were too high, advanced too tough. He wanted his students in bombers. Chico wanted no part of bombers. To prove he was fighter-pilot material drove him to excel in the cockpit and the classroom.

In the end, after many trying days, a washout rate approaching fifty percent, and long hours studying, Class 50D graduated. On March 29, 1950, some students earned the right to attend advanced flight training. In the end, Ogelsby believed Chico warranted the world of advanced fighters. Chico also made the newspaper back home: “Son of Mr. and Mrs. Pedro Solis, R.D. No. 2, Newtown, has recently completed basic pilot training at Goodfellow Air Force Base, San Angelo, Texas, and has been transferred to Las Vegas, Nevada, for advanced pilot training prior to receiving his silver pilot wings. Cadet Solis is a graduate of Richboro High School Class of 1948, where he was an outstanding athlete, having been awarded letters in baseball and soccer. He was also a member of the school aviation club and boys chorus.

Cadet Solis served with the U.S. Marine Corps from April 1946 to June 1947 as an aircraft mechanic. He enlisted in the Air Force in August 1948 and was transferred in July 1949 to Goodfellow Air Force Base for Aviation Cadet Training. His father presently operates the San Jose Poultry Farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.” (From a clipping, newspaper unknown)

Advanced would be the F-51 Mustang in the 3597th Pilot Training Squadron in the 3595th Pilot Training Wing, Nellis AFB, outside Las Vegas, Nevada. He was to report no later than April 3, 1950, and get on the stick … rudders and books. On base, he was given a room, sharing a common bath with another cadet named Albert Plecha. A merchant marine who wanted a change of pace, he chose fighters going from one extreme to another. The two became friends. And it was Al who bestowed the nickname “Chico” on introduction. Translated: boy. Roland looked so young.

The final phase, advanced pilot training, was rigorous. Students studied half days and flew Monday through Friday. Roll call was at 0500 with class or flying at 0700. Subjects were aircraft engineering, weather, navigation, principles of flight, aerophysics, flying safety, flight instruments, military law, including Air Force Administration and Organization. Cadets practiced formation flying, navigational, instrument, and acrobatics, performing stalls, rolls, barrel rolls, slow rolls, chandelles, Immelmann’s, spins, and inverted flying.

Now, knowing he was about to settle into what was the premier fighter just five short years prior, try to comprehend the emotion he felt standing on the tarmac, staring. In front of him waited an F-51. After his pre-flight inspection, nervous, he climbed up, strapped in, jostled the stick, feathered the rudder pedals, and familiarized himself with the gauge layout. Situated, he fired the Merlin. Rumbling to life, belching unburnt fuel, the twelve cylinders roared to life. Looking over the gauges, he felt the engine warming, smoothing out, relaxing.

Obtaining permission, he taxied to the runway, performing the required checks. Ready, he stared downwind, holding the brakes, while the Mustang begged for their release. Allowed to takeoff, he applied full throttle, maintaining brake pressure. The engine revved, ingesting air, devouring fuel, while pulling even more air through the propellor arc. A symphony of twelve cylinders, firing unmuffled, building to full crescendo, Chico, the conductor. An unmistakable sound! The Mustang pulled hard at the reigns to be let loose, trying to overcome the brake’s ability keeping the bird stationary. Holding the brakes, and his breath, Chico released. The propeller pulled, they rolled, slowly building speed, and the wings, building lift, created an air-war to become airborne.

On April 24, 1950, his childhood dream of flying fighters almost realized. What no one thought he could accomplish, was accomplished – almost. But the Mustang had a quirk. The engine produced power; so much it induced torque steer. If one wasn’t paying attention, the bird went right instead of where the pilot was looking. Using the rudder to compensate, Chico muttered: Don’t screw up, over and over while streaking down the runway. Gaining lift, he broke earth’s pull trying to keep him planted, flying towards heaven in the most powerful plane he had flown to date. He was in his element, the coveted spot he’d dreamed of since age five. He was fast becoming a full-fledged pilot. His heart was pounding as the Mustang awaited his inputs to perform in the manner it was accustomed. Right then, Chico felt the elation others had over the skies of Europe.

Weather dependent, flying took place in the morning or afternoon hours. Saturday flights transpired for lost weekdays due to adverse conditions. In the summer, temperatures regularly passed the century mark. On the tarmac, inside the cockpit with the canopy open, temps topped 120 degrees, even higher with the canopy closed. The polished aluminum skin was another danger. When the morning sun crested, equipment literally became too hot to touch. The Mustang had to get airborne quickly or it boiled over. And aside from touching one hot Mustang, things warmed elsewhere.

Chico spent his days training and weeknights in the barracks, allowed off base on weekends. Maria worked civil service and lived in a trailer not much more than a camper at the R&M Trailer Park. Free time, and money, precious and scarce. When allowed, they hung out at the Desert Inn, celebrating their wedding anniversary. Wilbur Clark opened the casino in 1950, inviting cadets to enjoy a friendly atmosphere. Able to use the curvaceous pool free of charge, Wilbur offered students free non-alcoholic drinks. The newest, most modern apparition in the desert, an oasis in an otherwise hot environment. One weekend with three bucks remaining, Maria played the nickel slots. Hoping good luck would save the day, she struck a twenty-five-dollar jackpot! Nickels tumbled everywhere. Feverishly gathering them, a gentleman with a large nose assisted. He was an actor, comedian, and jazz musician otherwise known as Jimmy Durante.

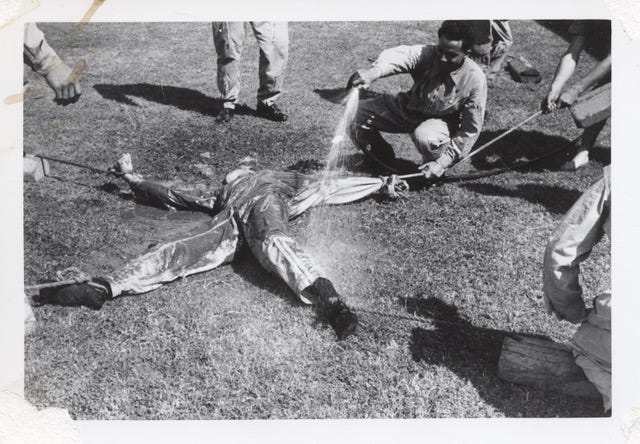

Well, on June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. Of the four classes at Nellis, three turned bomber, transferring to Texas. With those guiding hands still protecting, Chico’s class breathed a sigh of relief. Plus, with the upcoming war and graduation, cadets flew relaxed schedules. Time “in trail” with an instructor became routine, learning acrobatic maneuvers. In time, it would become Chico’s signature trait. On the fun side, practicing close formation flying without putting students in danger, entailed single file flying inside the Grand Canyon. If a raft were spotted on the river, tally-ho. The unsuspecting target allowed pilot trainees to practice strafing, seeing how close one could get, in a relaxed atmosphere. If someone on the raft bailed, mission accomplished! All while strapped in the seat of a Mustang.

Chico’s last advanced flight was July 20. Due to graduation, he was discharged on August 3rd to accept his commission on the 4th. Chico earned his wings, becoming a 2nd Lieutenant in the Reserves. In attendance were Kitty, his father Pedro, brother Peter, and one of Kitty’s brothers, Joe DeCosmo. The three drove in from Pennsylvania for the occasion. In 1949, through a car lay-a-way program, Maria purchased a brand-new Ford convertible making weekly installments. The car, albeit a year old, was presented at graduation. Chico also made the newspaper back home, with an interesting sentence:

The new Air Force training that he has received during the last thirteen months has prepared him to take over the controls of the giant bombers and transports of the United States Air Force and to take his place alongside graduates of the service academies at West Point and Annapolis. (From a clipping, newspaper unknown)